I have a dear friend Antony who is unable to throw anything away.

A senior partner for a leading City firm, I can proudly tell you he is a corporate real estate lawyer, revered and respected for his brilliance and integrity by clients and colleagues alike.

Unfortunately, his genius comes at a price. He is unable to part with memorabilia of any sort – Spurs’ programmes, theatre tickets, casual correspondence, unread magazines, recently read magazines, love letters, bank statements and utility bills stretching back decades. It is too heart-wrenching and anxiety-inducing for him to fill his car to make the trip to the local refuse tip. (Like he’d know where it was!)

He and I see the world through different lenses: mine neat, orderly and denuded of clutter, his chock-full of wistful memories and curiosity.

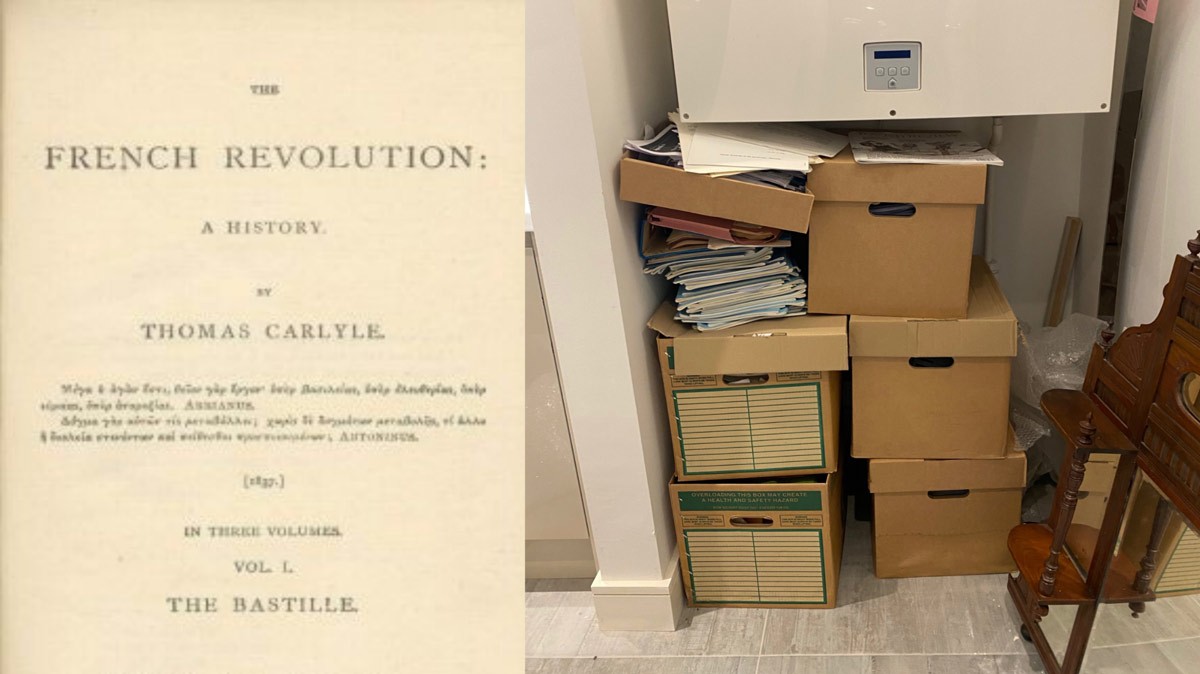

Antony has just had to endure significant personal turmoil. The firm where he has worked since 1987 is moving office, requiring him to choose what to bring to the new paper-free premises from his current room. After a major first tidy up and cull, its contents fitted neatly into 65 boxes. His long-suffering wife was out when he brought 18 of them home, surreptitiously storing them (as per the visual above) in less-frequented sections of his lovely house.

One day, he believes, you might need the decaying file at the bottom of Box 41, despite the plaintiff having died in 1989 and the defendant long-since decamped to a retirement home in Boca Rotan, Florida. He told me yesterday that he was vindicated by recently finding a 30 year old B&Q receipt for a radiator valve that helped him resolve a family property dispute. You just never know what you are going to need from the past, he would argue.

Which prompted me to tell him the story of Thomas Carlyle’s famous three volume history of The French Revolution.

In 1834, the philosopher John Stuart Mill took a hefty advance from a publisher to write a general history of the French Revolution but realised he was over-committed with other projects. He persuaded his friend Thomas Carlyle to write it instead. Coveting immediate fame, Carlyle bashed out Volume 1 in a determined frenzy of effort.

He sent it to Mill for review and awaited feedback. On the night of 6th March 1835, Mill turned up at Carlyle’s house in Cheyne Walk “the very picture of desperation.” Mill had left the manuscript with his friend Mrs Taylor, whose illiterate servant had used it to light a fire. All that was left were a few charred leaves and much embarrassment.

Carlyle, rather than resorting to his own version of revolutionary retribution, was the embodiment of reasonableness. He told Mill not to worry and that he would simply start again.

After Mill departed, his first word’s to his wife were “ … the poor fellow is terribly cut up. We must endeavour to hide from him how very serious this business is for us.” He desperately needed the money but more worryingly, for some reason he had destroyed his notes and declared “I remember and can still remember less of it than of anything I ever wrote with such toil. It is gone.”

That night, providentially, he was visited in his sleep by his dead father and brother, who told him not to be such a wimp and get on with writing it again. He asked Mill the next morning for some money which he used to buy paper and got to work. He wrote Volumes 2 and 3 and then by some miracle, re-produced the first from memory, or as he put it poetically “directly and flamingly from the heart.” It was published to significant and universal acclaim and the rest is history. (French Revolutionary history that is.)

If Carlyle had Antony’s byzantine filing system, he would have been spared a lot of angst. His ambition, however, had told him once a task is completed to move forward free from the clutter of the past.

Which is the right approach?

Microsoft servers buried somewhere in the ocean have allowed us to store our commercial lives without recourse to endless reams of environmentally unfriendly paper. Wherever we chose to sit, from coffee-shop to a garden, will be the scene of our greatest triumphs or disasters. You don’t need a cluttered desk to show you are busy or important.

But memories also need to be tangible. We want to hold them in our hands without having to rely simply on the hard drive of our laptops. We should talk about them and process the contribution they have made to the narrative of our careers.

The evidence of our accomplishments has to be easily retrieved, whether virtual or in print. Let’s celebrate the moments that got us to this point. Our personal histories are the foundation of our future experiences. We need to be reminded of mistakes and re-acquainted with moments of long-forgotten triumph.

So, corporate sentimentality and nostalgia can be healthy. Whilst Antony’s 65 boxes may be excessive, they are testament to the successes and failures that have shaped him and his desire to learn as he progresses in his career. Thomas Carlyle could have saved himself a lot of candle-lit late nights if he had treated his research with similar reverence.

Of course, I am not actually condoning his ludicrous hoarding. Being a collector of dental gum imprints, menu cards from formal dinners and the internal phone list 1991 is nothing to celebrate. It’s a bloody illness.