If you read this article, I promise not to bore you with prophecies of our collective future.

I appreciate that we are all brainstorming continually how to avoid commuting, flying Easy Jet or enjoying a cheeky Nandos again. Not a day goes by, without an article that explains how from now on, we will be working from home and in our office concurrently, whilst socially distancing from our colleagues and going to work on a unicycle to avoid the tube. Enough already. The coming weeks are not going to answer meaningful questions about how we will all make a living going forward.

Yet, we scenario plan with ferocity. Not only that, we post our speculative thoughts to an equally speculating world and the R value of our cumulative speculation, is well above the dangerous level of 1. (If you don’t know what the R value is, you have obviously not been studying virology like the rest of us.)

For those of you committed to reading your horoscope, what I am going to reveal may be offensive, for which I apologise. If it is any consolation, you are definitely going to meet a tall, dark, handsome stranger and I predict they will be almost certainly be wearing a mask.

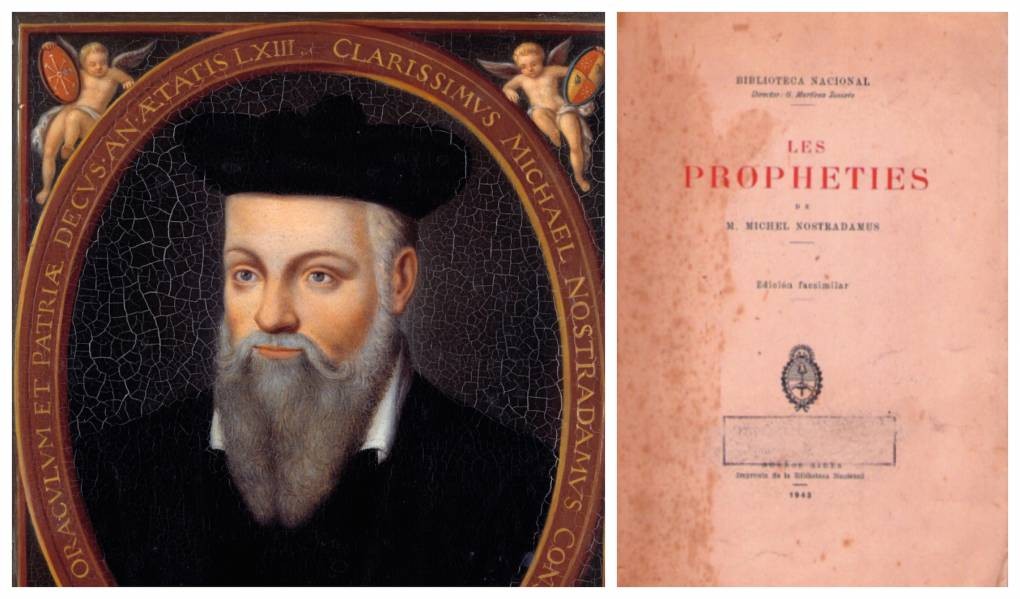

Let’s look at the most famous seer in history to prove my point.

Nostradamus (1503-66) was a French astrologer, physician and world-champion predicter of catastrophes. His real name was Michel de Nostradame, which he clearly thought was not nearly mysterious enough, so he upped the Latin to make it punchier. His most famous work was Les Prophetes, a collection of 942 verses allegedly predicting future events.

Co-incidentally, he lived during a time of recurring plague. His university studies at the University of Avignon were curtailed due to an outbreak which tragically killed his wife and his two daughters some two years later. Perhaps the severity of his experience made him want to see a brighter future. And yet the predictions for which he best-known were all pretty bleak moments of human history.

Most of the writing deals with disasters, such as plagues, earthquakes, wars, floods, invasions, droughts and battles. His supporters allege that he foresaw ‘The Fire of London’, ‘The French Revolution’, the rises of Napoleon and Adolf Hitler, both world wars, the nuclear explosions in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the death of Princes Di and 9/11. If this was true, he clearly had a top of the range crystal ball.

Years of contextual analysis supporting his clairvoyance have unravelled since 1980, when academics began to show that much of what was claimed about Nostradamus did not match documented facts. The prevailing view is that the vagueness of his predictions have been retrospectively shaped to fit actual events. Scholars also point out that almost all the historical translations into English are extremely poor quality, show little knowledge of 16th Century French and sometimes, have been intentionally altered to make them suit the whims of the translator.

Without entering an academic debate for which I am unqualified, (my 16th Century French is not that good, although better than my 13th Century Spanish) there is an interesting parallel to be drawn with current futurology.

Yes, it’s all a bit grim at present, but in the absence of certainty, we are in danger of anticipating events which may not happen. Human nature craves re-assurance, but before we deliver a vision for our worrying future, we should pause if possible to make sure that we are dealing with all the facts not trying to guess a language with which we are unfamiliar.

All businesses have to anticipate unpredictable scenarios and take immediate action, that of course is obvious. More concerning are the corporate seers trying to guide those organisations by outlining situations impossible to currently call.

We need to differentiate between immediate trading necessity and creating a new vision for business sometime hence. Nostradamus allegedly achieved a trance-like state that allowed him to see the cracks in the pavement which would trip hundreds of years later. What made people support his prophecies was an innate desire to believe we are part of a divine plan, not the victims of the random cruelty of the cosmos.

You can believe whatever you want about the next bumpy period, but our interdependent well-being will be predicated on our ability to adapt spontaneously not to predict in advance. That’s what my tea leaves say anyway.

In the meantime, my stomach is rumbling. Gazing in to the future, I can safely say it must be time for some lunch.